You can’t change the hair color after you shoot: a Q&A with Cami Kwan, stop-motion animator and director

"You’re going to have to compromise somewhere unless you have unlimited money and like five Oscars behind you."

Welcome to Revisionary, a Q&A series where artists talk about revising, redoing, and how to make what you create even better.

I’ve always loved stop-motion animation. I grew up on Gumby and Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, and Wallace and Gromit. There’s something about it that makes the experience of watching a show almost tactile. I have a friend who works in the industry so I asked him whose work he admires. One of the first names that came up was Cami Kwan.

Cami is so cool, y’all! Her work is gorgeous. She co-owns an independent animation studio. She is creating and directing a stop-motion animated short film called “Paper Daughter” based partially on her great-grandmother’s experience of immigrating from China at Angel Island in the 1920s. (Cami is running a crowd-funding campaign for it through July 2nd. Even if you don’t have money to give, it’s worth watching the video just to see the beautiful story she’s creating!)

I’m thrilled to be kicking off this new Q&A series, Revisionary, with Cami who was kind enough to talk to me on a weekend to make this happen!

Read on for why you should articulate the core of every creative project you make, the double-edged sword of getting to be a creative professional, and why compromise might be the best tool in your revision playbook.

TD: Can you introduce yourself and talk about the work you do?

Cami Kwan: I'm a stop motion director primarily, and I'm a co-owner of an independent animation studio called Apartment D. We specialize in stop motion animation. We also do other types of animation but stop motion is our bread and butter. So my main focus is creating stop motion animated projects for young adults and kids. The new personal project I’m working on is a little aged-up. It’s kind of a gothic fairy tale about Chinese immigration in the 1920s.

TD: In writing, when I talk about making a piece better I talk about revising it. Is there a word you use in stop motion? How do you think about going in and improving on things?

CK: That’s such an interesting question. I think revising is totally a valid descriptor. For us, there are three main phases of production. There's pre-production, production, and post-production. Pre-production is the most effective place to do that revision and make sure things are kind of looking and feeling the way that we ultimately want them to. Pre-production includes writing the scripts and making an animatic [drawing storyboards for all the actions and turning them into a video format]. So it's kind of like a comic book sketch video version of what the final product would be. The step also includes production design, figuring out what all the environments and props are going to look like, as well as character design, figuring out exactly what the characters are going to look like.

That pre-production process is the place where it's easiest to make changes because we haven't built anything yet. It's all highly theoretical and highly editable. So that's where revisions happen the most.

Then I guess with stop motion, there's a middle phase of fabrication that comes between pre-production and production. We're building the sets, we're building puppets. So there is some amount of revision that can happen there. But there are set points where you can’t go back on anything you’ve chosen from that point forward. You can’t, like, change the hair color after you’ve shot it.

“You can be the most creative, visionary director in the world, but if you're unwilling to compromise on your initial vision, your film might not get made. Are you even a director if your film didn't get made, you know?”

-Cami Kwan

TD: Can you tell me about a piece you worked on lately that wasn't working and how you approached that?

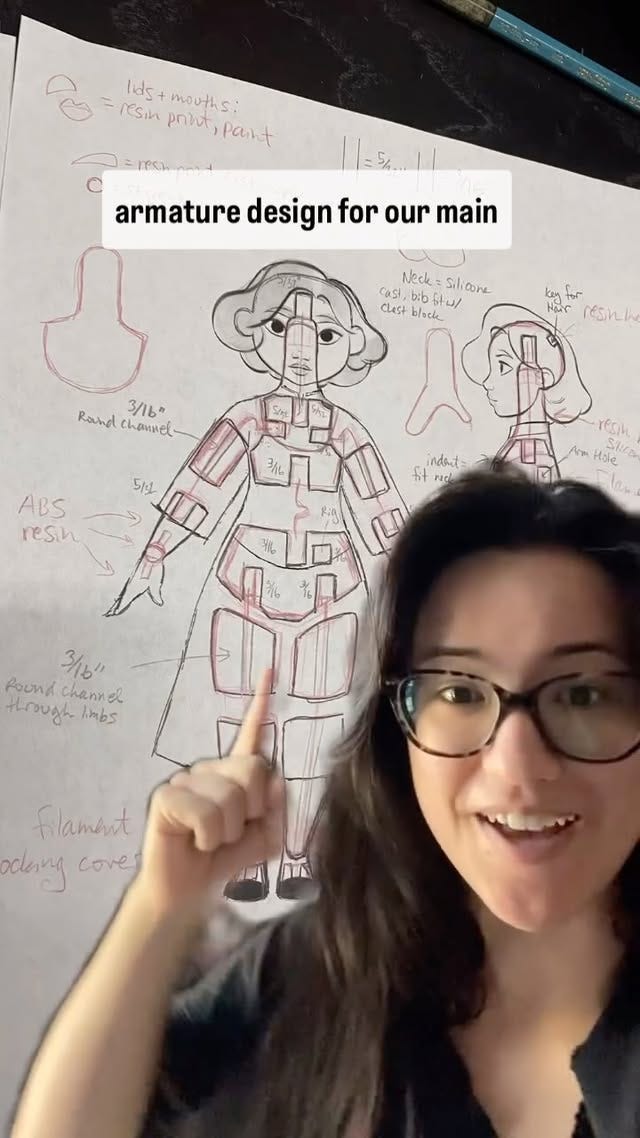

CK: Right now in my personal film, “Paper Daughter” we’re making the puppets in a way that I've never made puppets before. We're trying out a much more integrated combination of 3D printing with traditional stop motion puppet making. And there are a lot of new mechanisms that we're trying. And there's a lot more back and forth between the 3D modelers, 3D printers, and the fabricators.

A lot of our initial thoughts about how we were going to build these armatures—an armature is like the skeleton inside of the puppet—are not necessarily panning out when we're printing them out at the actual scale. These puppets are seven inches tall, which is a little on the small side.

We're doing things like printing out like joints for the wrist, which you can imagine are quite tiny. So it's a lot of talking—it's so much communication and checking in with the fabrication team and being like, “okay, what about this joint is not working for you guys” and getting their feedback. And then I'll go to the modelers and see what what levers we can pull to address the issues that are coming up.

We need to make space for the joint to be bigger but we can’t without changing the core look of the character. The character designer designed it that way because I, the director, told them to do it that way. So it's all back to me.

It's like, which aspects am I willing to compromise on to like make this puppet animatable?

It’s really representative of everything that has ever gone wrong in any project I've done. It all comes down to like communication and compromise, figuring out where the problems are.

TD: That feels like so many moving parts to have to deal with. Coming up with a story and a character is hard enough and the part I can relate to. But then having to change it for technical reasons? That seems so hard.

CK: I think that's one of the really interesting things about being a director. Like I think we hear like the director of the film and we think like, it's a mad genius! They're just coming up with ideas! They're so creative! But I think like for anything that's coming into a physical reality—so probably any form of animation, especially stop motion, things like live action—once you do that initial creative work, in the pre-production and the writing and the everything, most of the rest of your job is just executing it and figuring out like, what do you need to do to land as close to your initial creative vision as you possibly can?

You’re going to have to compromise somewhere unless you have unlimited money and like five Oscars behind you. You have to. I think the job of directing is mostly making creative solutions and creative compromises to get the film made as close to what your original vision is as possible.

TD: And within budget, which is less fun.

CK: Budget within the schedule. That's a skill in and of itself. You can be the most creative visionary director in the world, but if you're unwilling to compromise on your initial vision, your film might not get made. Are you even a director if your film didn't get made, you know? If a tree falls in the forest.

I think that ability to communicate and compromise is so core to being a professional creative.

“Throughout the script when I was like, ‘this part isn’t working,’ I’d look back and say, ‘What is this section telling us about that core message?’

If what you're doing is not serving that, then either it needs to change or it needs to go.”

-Cami Kwan

TD: This might sometimes be an obvious answer, but how do you know when something isn't working when you're working on a project?

CK: I guess there's two aspects to that. There's the physical for stop motion. It's like, is it physically not working? Like, can this thing not bend the way we thought it would? Is this thing breaking if you just look at it wrong?

But from a more like creative and emotional aspect if people are getting distracted by something other than the story that you're trying to tell, then it's not working. If people are getting bored halfway through or starting to really hone in on like, “oh, that dress looks really wrinkly,” then they're not watching the story. They're looking at other things. And that's a big problem when I notice things like that.

I still maintain that love of stop motion and that wonder and that awe of seeing something move. If I'm not getting swept away by the performance, I know that there's something off. The animatic phase of our productions is probably one of the most important things for figuring out if something's not working from a creative or emotional or storytelling perspective.

TD: When something isn’t working, I feel like you have the options of: keep trying things or give up. How often do you just give up on an idea or part of something you’re trying?

CK: Some projects have space to keep trying in the budget and schedule and some projects just don't. It's a lot of looking at the schedule, frankly. Every project I do try to do something new with the puppets or sets or animation. I look at the schedule and see we have wiggle room to do one more day to make the shot work and then we have to stop because it needs to keep going to stay on track.

To be honest, I don’t think I’ve had the luxury of being able to work on something until it’s perfect for the sake of it being the best version it can be—which sucks. That’s one of the drawbacks of being creative professional; you don't get to work on things until they're absolutely perfect because you are a professional. I have to answer to people; there's money attached; there's expectations attached.

The double-edged sword of being a creative professional is that you always have to answer to something beyond the art itself.

TD: Do you have any advice for someone who is struggling with something where they're like, this just isn't working? What would you tell someone?

CK: I think when you're in that situation, the best thing you can do is go back to what is the core of this project? What is the core emotional message here? What is the most important thing to me that people take away?

I don’t remember where I got that advice, but at some point someone told me to write out the core of your project and put it down where you could see it. Whenever you’re stuck, look at that.

For “Paper Daughter” it’s exploring the ways to make peace with guilt from receiving someone else’s sacrifice. So I wrote that down and put it off to the side. Throughout the script when I was like, “this part isn’t working,” I’d look back and say, “What is this section telling us about that core message?”

If what you're doing is not serving that, then either it needs to change or it needs to go.

TD: What is inspiring you lately in your own work or like where do you turn for inspiration?

CK: In the entertainment industry everything’s on fire. Everybody’s merging with everybody. Everybody’s trying to make everything AI. It feels so disheartening to continue working in this space but what I’m really inspired by is the rise of independent animation. It is so vibrant. It is so alive right now.

I see weird projects that would never have been green-lit anywhere else exploding and succeeding. That makes me so happy to know that audiences are there for the weird stuff. They're there for those like hyper-unique, specific, stylized funky stuff.

It encourages me to be like, “you know even if the things I’m making are not ‘commercially viable’ that doesn’t mean there’s not a place for them.” You’re not going to make a hundred billion dollars the way that your big studios do but you don't need to make a hundred billion dollars. Like you're a small team of 12 people making this thing. So you only need to make like however much to support those 12 people, you know?

But where I turn to for inspiration: I really am a big fan of turning outside of film to be inspired to make your film and outside of animation to be inspired to make animation. Just going to an art museum is awesome. Or I'm a big metal fan and when you’re at a concert in the midst of a crowd and you lost all your friends, you're just by yourself, you're like focusing on the music, it really frees you up to actually think.

TD: I might know what you want to talk about for this, but can you talk about a favorite piece you're working on or just completed and like why it's exciting to you?

CK: I’m working on a short film called “Paper Daughter” and it is based on the immigration experience of my great grandmother. She immigrated to the US from China in 1926 via the West Coast immigration station called Angel Island. Angel Island was for immigrants coming into San Francisco and the better known Ellis Island was for immigrants into New York and primarily Asian immigrants came through Angel island.

“Paper daughter” refers to something that was fairy common in immigration from China because it was the height of the Chinese Exclusion Act. It was very difficult to get into the US unless you were of a certain class or another wealthy type of individual. If you happened to be lucky enough to have family that already lived here, there were certain laws that would allow family members to come over.

A lot of people came over under assumed identities, either identities of people who had died, or in the big earthquake and fire in San Francisco in the late 1800s, some people reported additional descendants. So you were coming over as this fictitious descendant.

The film is about living with the guilt of your future being secured by someone else’s sacrifice that you’ll never be able to repay. So, in this story, it's about a girl who is immigrating under the identity of a deceased girl.

And that mirrors the guilt that a lot of children of immigrants feel where like, there's nothing we can do to repay those sacrifices because those ancestors, those family members have passed. Like, how do I justify having the opportunities that I have when other people don't?

This is the 100-year anniversary of my great grandmother's immigration. And unfortunately, 100 years hence, the situation for immigrants is no better than it was then.

I'm really excited to be creating something in stop motion, which is a format that I absolutely am so passionate about, and to be creating something that is unfortunately still so relevant.

With DEI being on the chopping block around the world, it’s a real privilege to be making a women-led, minority-led film in an industry that’s fairly dominated by white men. Stop motion is not necessarily the most diverse place to be. So to be able to bring a project like this to life with artists that it’s about is really fantastic.

Thank you again to Cami Kwan for taking part in this interview. You can follow her work on Instagram and check out and support the making of her film “Paper Daughter”! The crowdfunding campaign is live until July 2.

If you enjoyed this interview, please share with others and subscribe to get future issues in your mailbox.

I’ll be back in two weeks with another Revisionary interview!

If you want to suggest someone I should interview for this series, please comment below with a name and where to find them. If you’re interested in being interviewed for this series, please fill out this form.

You can directly support my work by upgrading to a paid subscription to A Little Detour, sharing this post with someone who might enjoy it, or buying a copy of my book Under the Henfluence. If you love this newsletter but can’t afford to become a paid subscriber, send me an email to get a comped subscription. I’m just happy you’re here!

Because all writers have a never-ending hope of finding ways to make writing financially sustainable, I’ve opened a Bookshop.org affiliate page. If you buy any of the books I mention in this newsletter, I will get a small commission and will use it to buy myself more books.